16.4. Lesson: Spatial Queries

Spatial queries are no different from other database queries. You can use the geometry column like any other database column. With the installation of PostGIS in our database, we have additional functions to query our database.

The goal for this lesson: To see how spatial functions are implemented similarly to “normal” non-spatial functions.

16.4.1. Spatial Operators

When you want to know which points are within a distance of 2 degrees to a point(X,Y) you can do this with:

select *

from people

where st_distance(geom,'SRID=4326;POINT(33 -34)') < 2;

Result:

id | name | house_no | street_id | phone_no | geom

----+--------------+----------+-----------+---------------+---------------

6 | Fault Towers | 34 | 3 | 072 812 31 28 | 01010008040C0

(1 row)

Note

geom value above was truncated for space on this page. If you want to see the point in human-readable coordinates, try something similar to what you did in the section “View a point as WKT”, above.

How do we know that the query above returns all the points within 2 degrees? Why not 2 meters? Or any other unit, for that matter?

Answer

The units being used by the example query are degrees, because the CRS that the layer is using is WGS 84. This is a Geographic CRS, which means that its units are in degrees. A Projected CRS, like the UTM projections, is in meters.

Remember that when you write a query, you need to know which units the layer’s CRS is in. This will allow you to write a query that will return the results that you expect.

16.4.2. Spatial Indexes

We also can define spatial indexes. A spatial index makes your spatial queries much faster. To create a spatial index on the geometry column use:

CREATE INDEX people_geo_idx

ON people

USING gist

(geom);

\d people

Result:

Table "public.people"

Column | Type | Modifiers

-----------+-----------------------+----------------------------------------

id | integer | not null default

| | nextval('people_id_seq'::regclass)

name | character varying(50) |

house_no | integer | not null

street_id | integer | not null

phone_no | character varying |

geom | geometry |

Indexes:

"people_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (id)

"people_geo_idx" gist (geom) <-- new spatial key added

"people_name_idx" btree (name)

Check constraints:

"people_geom_point_chk" CHECK (st_geometrytype(geom) = 'ST_Point'::text

OR geom IS NULL)

Foreign-key constraints:

"people_street_id_fkey" FOREIGN KEY (street_id) REFERENCES streets(id)

16.4.3. Try Yourself: ★★☆

Modify the cities table so its geometry column is spatially indexed.

Answer

CREATE INDEX cities_geo_idx ON cities USING gist (geom);

16.4.4. PostGIS Spatial Functions Demo

In order to demo PostGIS spatial functions, we’ll create a new database containing some (fictional) data.

To start, create a new database (exit the psql shell first):

createdb postgis_demo

Remember to install the postgis extensions:

psql -d postgis_demo -c "CREATE EXTENSION postgis;"

Next, import the data provided in the exercise_data/postgis/ directory.

Refer back to the previous lesson for instructions, but remember that you’ll

need to create a new PostGIS connection to the new database. You can import from

the terminal or via DB Manager. Import the files into the following database

tables:

points.shpintobuildinglines.shpintoroadpolygons.shpintoregion

Load these three database layers into QGIS via the Add PostGIS

Layers dialog, as usual. When you open their attribute tables, you’ll note

that they have both an id field and a gid field created by the

PostGIS import.

Now that the tables are imported, we can use PostGIS to query the data. Go back to your terminal (command line) and enter the psql prompt by running:

psql postgis_demo

We’ll demo some of these select statements by creating views from them, so that you can open them in QGIS and see the results.

Select by location

Get all the buildings in the KwaZulu region:

SELECT a.id, a.name, st_astext(a.geom) as point

FROM building a, region b

WHERE st_within(a.geom, b.geom)

AND b.name = 'KwaZulu';

Result:

id | name | point

----+------+------------------------------------------

30 | York | POINT(1622345.23785063 6940490.65844485)

33 | York | POINT(1622495.65620524 6940403.87862489)

35 | York | POINT(1622403.09106394 6940212.96302097)

36 | York | POINT(1622287.38463732 6940357.59605424)

40 | York | POINT(1621888.19746548 6940508.01440885)

(5 rows)

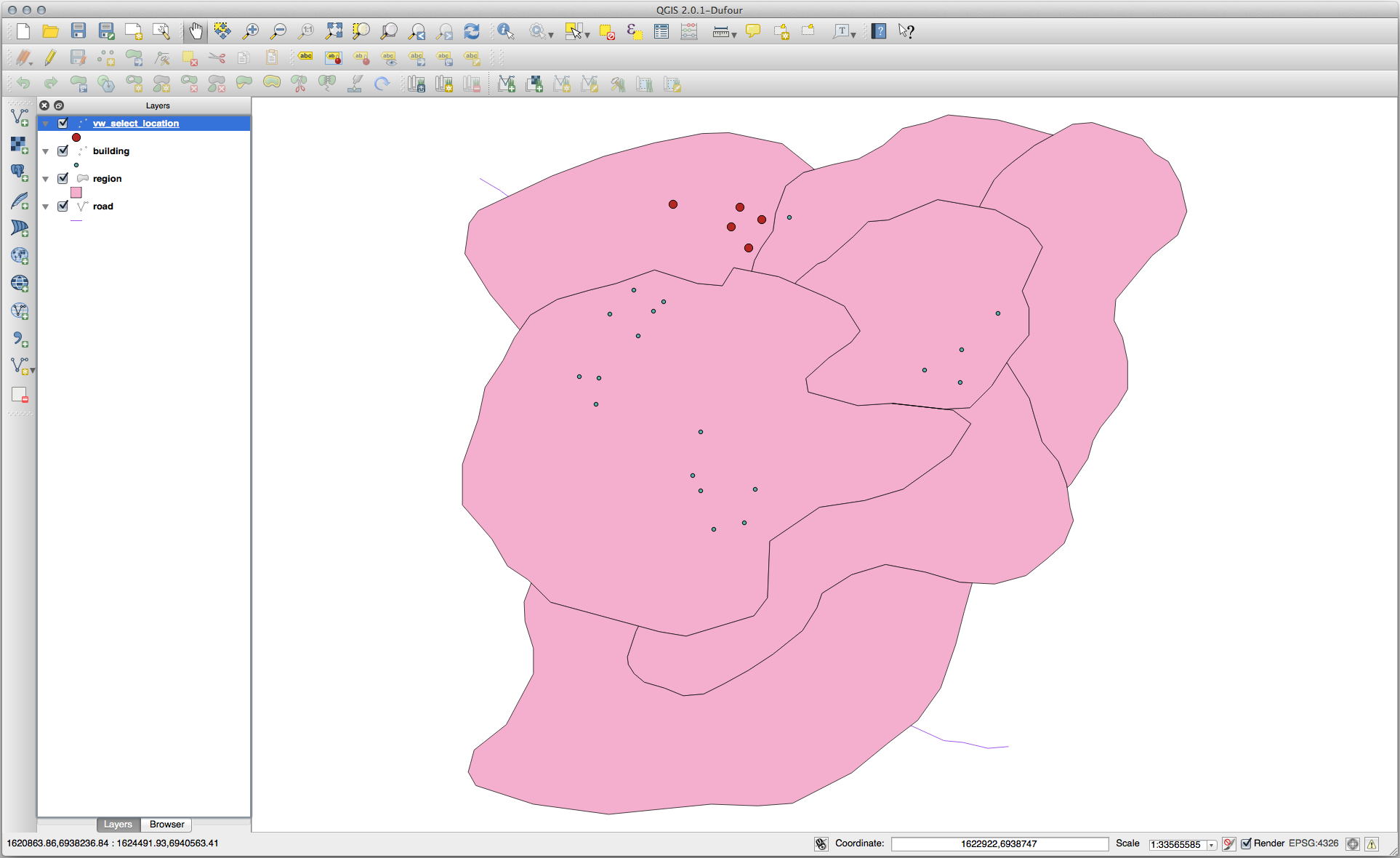

Or, if we create a view from it:

CREATE VIEW vw_select_location AS

SELECT a.gid, a.name, a.geom

FROM building a, region b

WHERE st_within(a.geom, b.geom)

AND b.name = 'KwaZulu';

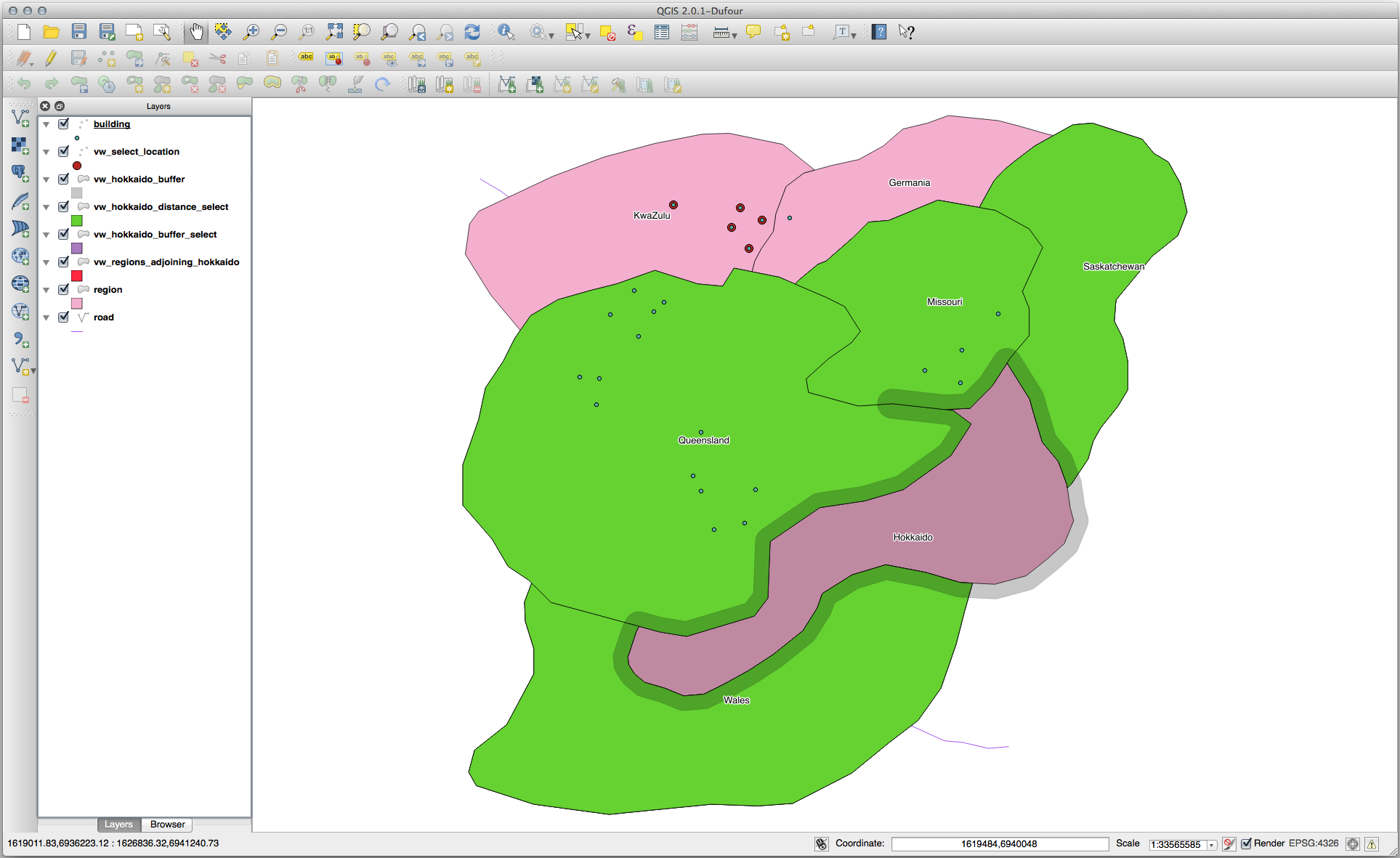

Add the view as a layer and view it in QGIS:

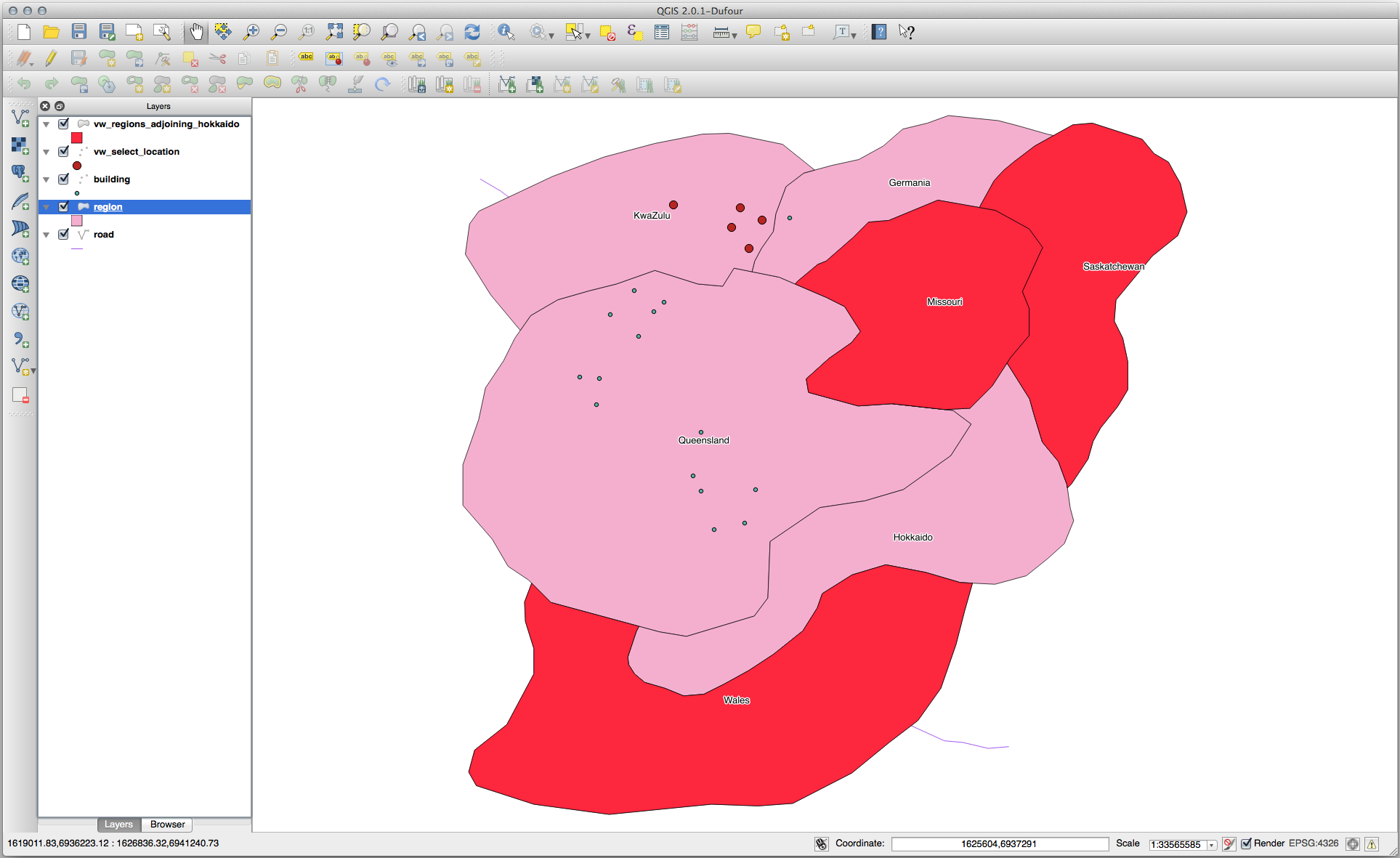

Select neighbors

Show a list of all the names of regions adjoining the Hokkaido region:

SELECT b.name

FROM region a, region b

WHERE st_touches(a.geom, b.geom)

AND a.name = 'Hokkaido';

Result:

name

--------------

Missouri

Saskatchewan

Wales

(3 rows)

As a view:

CREATE VIEW vw_regions_adjoining_hokkaido AS

SELECT b.gid, b.name, b.geom

FROM region a, region b

WHERE st_touches(a.geom, b.geom)

AND a.name = 'Hokkaido';

In QGIS:

Note the missing region (Queensland). This may be due to a topology error. Artifacts such as this can alert us to potential problems in the data. To solve this enigma without getting caught up in the anomalies the data may have, we could use a buffer intersect instead:

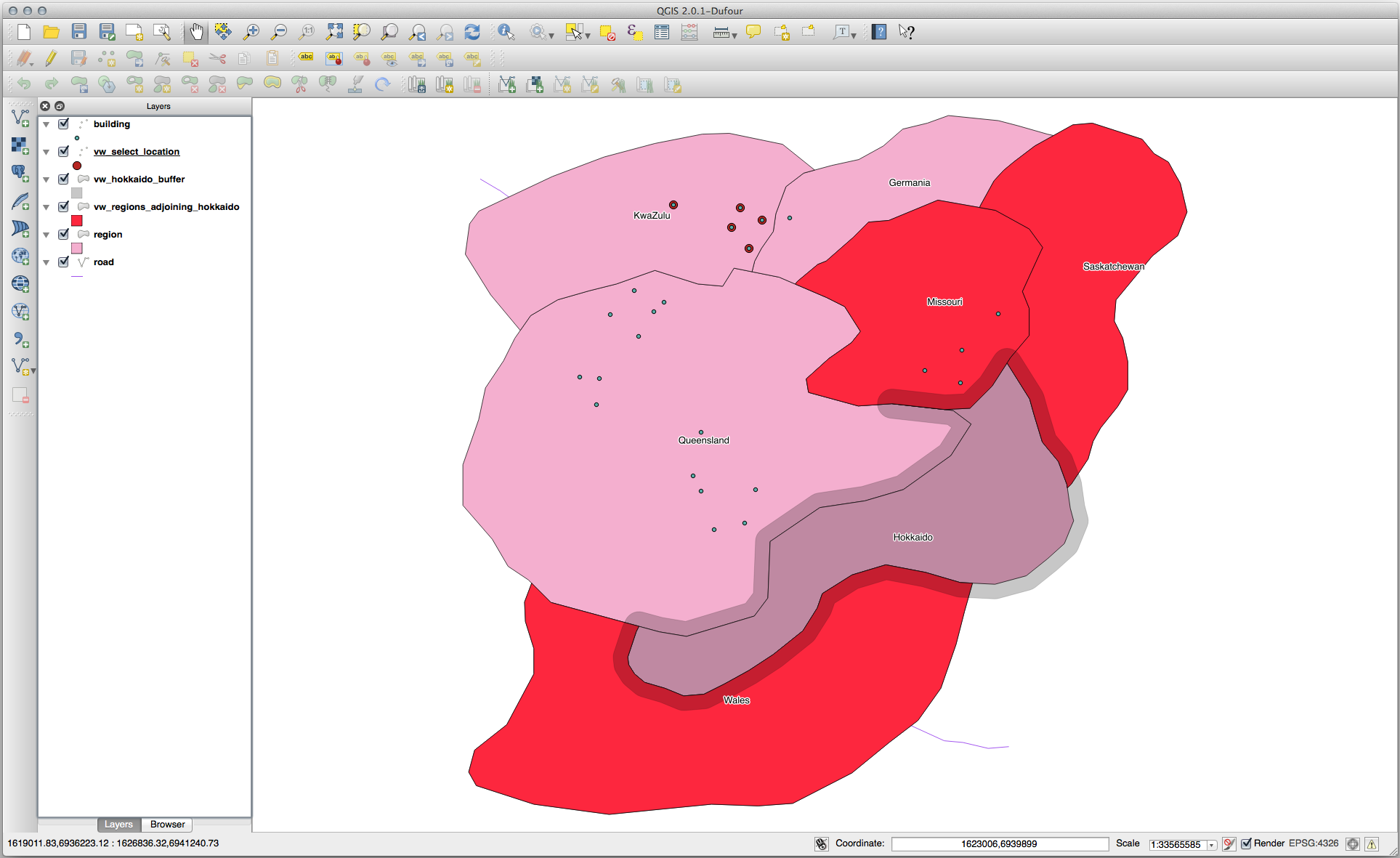

CREATE VIEW vw_hokkaido_buffer AS

SELECT gid, ST_BUFFER(geom, 100) as geom

FROM region

WHERE name = 'Hokkaido';

This creates a buffer of 100 meters around the region Hokkaido.

The darker area is the buffer:

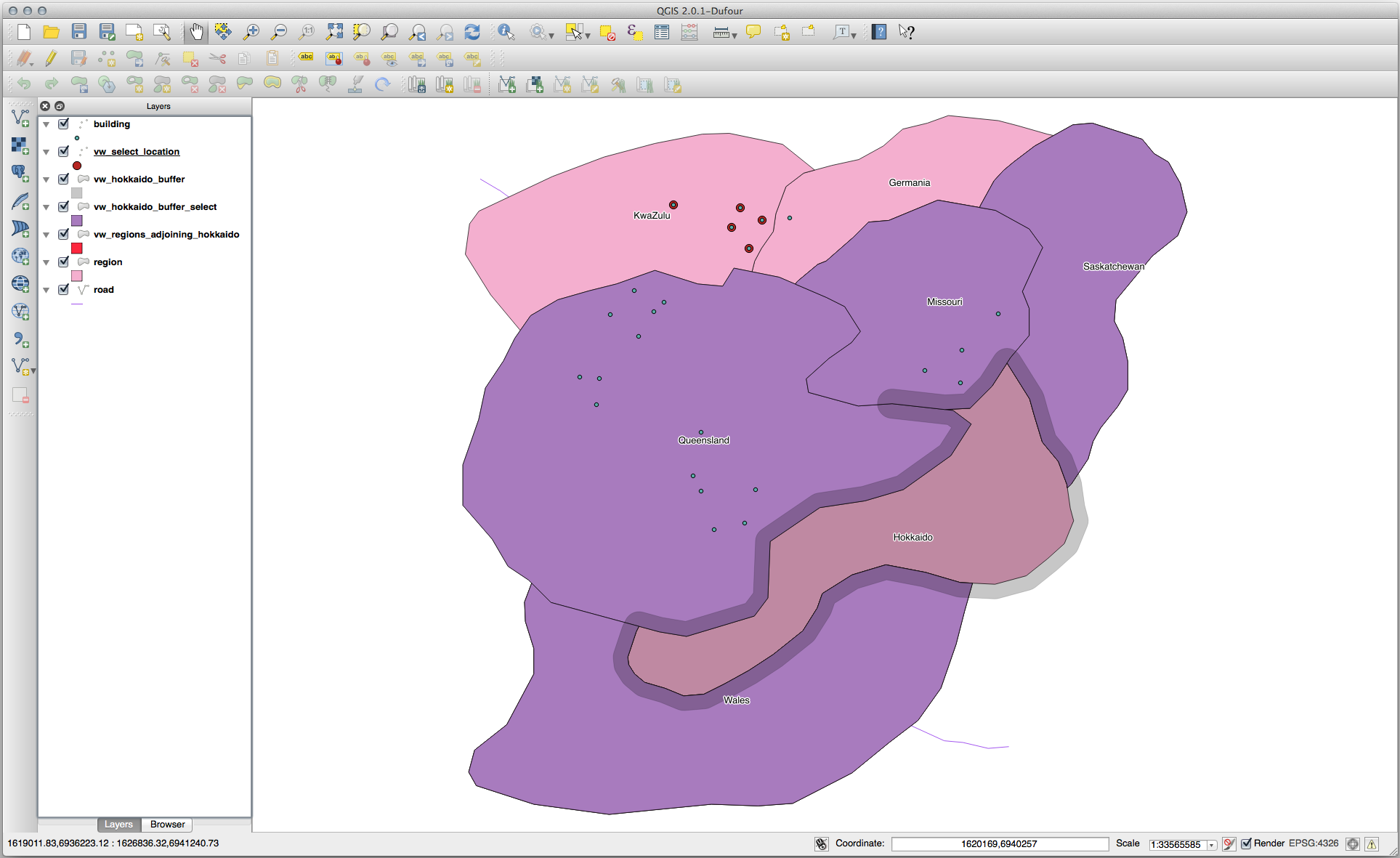

Select using the buffer:

CREATE VIEW vw_hokkaido_buffer_select AS

SELECT b.gid, b.name, b.geom

FROM

(

SELECT * FROM

vw_hokkaido_buffer

) a,

region b

WHERE ST_INTERSECTS(a.geom, b.geom)

AND b.name != 'Hokkaido';

In this query, the original buffer view is used as any other table would be. It

is given the alias a, and its geometry field, a.geom, is used

to select any polygon in the region table (alias b) that

intersects it. However, Hokkaido itself is excluded from this select statement,

because we don’t want it; we only want the regions adjoining it.

In QGIS:

It is also possible to select all objects within a given distance, without the extra step of creating a buffer:

CREATE VIEW vw_hokkaido_distance_select AS

SELECT b.gid, b.name, b.geom

FROM region a, region b

WHERE ST_DISTANCE (a.geom, b.geom) < 100

AND a.name = 'Hokkaido'

AND b.name != 'Hokkaido';

This achieves the same result, without need for the interim buffer step:

Select unique values

Show a list of unique town names for all buildings in the Queensland region:

SELECT DISTINCT a.name

FROM building a, region b

WHERE st_within(a.geom, b.geom)

AND b.name = 'Queensland';

Result:

name

---------

Beijing

Berlin

Atlanta

(3 rows)

Further examples …

CREATE VIEW vw_shortestline AS

SELECT b.gid AS gid,

ST_ASTEXT(ST_SHORTESTLINE(a.geom, b.geom)) as text,

ST_SHORTESTLINE(a.geom, b.geom) AS geom

FROM road a, building b

WHERE a.id=5 AND b.id=22;

CREATE VIEW vw_longestline AS

SELECT b.gid AS gid,

ST_ASTEXT(ST_LONGESTLINE(a.geom, b.geom)) as text,

ST_LONGESTLINE(a.geom, b.geom) AS geom

FROM road a, building b

WHERE a.id=5 AND b.id=22;

CREATE VIEW vw_road_centroid AS

SELECT a.gid as gid, ST_CENTROID(a.geom) as geom

FROM road a

WHERE a.id = 1;

CREATE VIEW vw_region_centroid AS

SELECT a.gid as gid, ST_CENTROID(a.geom) as geom

FROM region a

WHERE a.name = 'Saskatchewan';

SELECT ST_PERIMETER(a.geom)

FROM region a

WHERE a.name='Queensland';

SELECT ST_AREA(a.geom)

FROM region a

WHERE a.name='Queensland';

CREATE VIEW vw_simplify AS

SELECT gid, ST_Simplify(geom, 20) AS geom

FROM road;

CREATE VIEW vw_simplify_more AS

SELECT gid, ST_Simplify(geom, 50) AS geom

FROM road;

CREATE VIEW vw_convex_hull AS

SELECT

ROW_NUMBER() over (order by a.name) as id,

a.name as town,

ST_CONVEXHULL(ST_COLLECT(a.geom)) AS geom

FROM building a

GROUP BY a.name;

16.4.5. In Conclusion

You have seen how to query spatial objects using the new database functions from PostGIS.

16.4.6. What’s Next?

Next we’re going to investigate the structures of more complex geometries and how to create them using PostGIS.